Exploring Indigenous Identity & Perspective

Meet four contemporary Native American artists whose unique viewpoints are redefining art history.

This article originally appeared in Artists Magazine. Subscribe now so you don’t miss any great art instruction, inspiration, and articles like this one.

The art of Native American people has always been deeply entwined with their daily lives, inherently part of their culture. The physical appearance of an object resulted, in part, from its intended use instead of an esoteric, purely aesthetic or personal meaning placed upon it by individual artists.

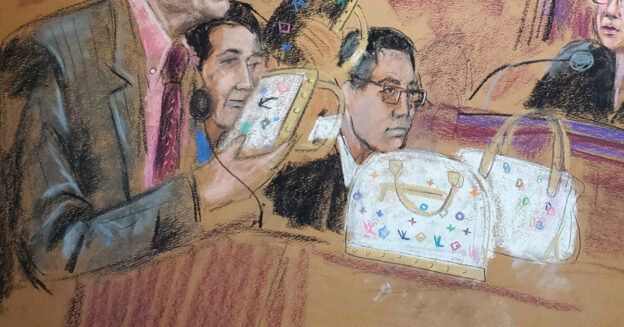

Early imagery and objects created by Indigenous artists and artisans included pottery, baskets, blankets, jewelry and clothing. Promoted through formulated art fairs and cultural expositions, these objects were removed from the realm of the useful and practical to became collectible remnants of a “lost” culture that established a fixed perception of Native identity (see “A Formulated World”).

Today, the work of contemporary Indigenous artists is being re-examined and recognized within the context of art history. The work is no longer being considered as an offshoot of ethnography or relegated to “craft,” but rather lives within the realm of fine art. Unlike their ancestors, today’s artists are identified by name as individuals with distinctive and geographically varied tribal associations. Their work often has political, historical and environmental overtones that reference the realities of their lived experiences.

Native American artists are now seen—and appreciated—as contemporary artists who are producing work that’s uniquely personal, creating art that helps us understand the world we live in today. Here are four outstanding Indigenous artists you should know.

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith

Jaune Quick-to-See Smith, a citizen of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes, is one of the most significant Native artists working today. Born on a Montana reservation in 1940, her first name, Jaune, means “yellow” in French, alluding to her dual French-Cree ancestry. She was a child of poverty, but her creative ability took her to the University of New Mexico, where she earned an MFA in 1980.

Now, she’s the first Native American artist to curate an exhibition at the National Gallery of Art (NGA), in Washington, D.C. The exhibition, “The Land Carries Our Ancestors: Contemporary Art by Native Americans,” runs from September 24, 2023, through January 15, 2024, before traveling to the New Britain Museum of American Art, in New Britain, Conn. By choosing to feature 50 living Indigenous artists, including a number whose works were recently acquired by the museum, the artist is paying it forward, bringing public attention to them.

Smith’s curatorial turn comes at a moment of long-overdue institutional recognition. Her wide-ranging practice, rooted in painting and collage, fuses the visual language of Abstract Expressionism and Pop Art with Neo-Expressionist energy and her own Native history. In 2020, NGA acquired her iconic painting, I See Red: Target; the first painting by a Native American artist to enter its collection since the museum’s founding in 1937.

Now in her 80s, Smith’s lifelong experience as an art educator, arts advocate and political activist is the subject of a career retrospective that runs through August 13 at the Whitney Museum of American Art, in New York City, titled “Jaune Quick-to-See Smith: Memory Map.” In mixed media work such as I See Red: The Vanishing American, Smith blends acrylic, newspaper, paper, cotton, printing ink, chalk and graphite pencil into a powerful image dominated by red and black markings that explode on the canvas. Horses frequently appear in her paintings and drawings in various guises. War Horse in Babylon, the thought-provoking anti-war diptych, makes direct reference to Picasso’s Guernica in the pieta-like image of the screaming woman holding a body in the lower right-hand corner.

“My life’s work involves examining contemporary life in America and interpreting it through Native ideology,” Smith says in a statement about the Whitney retrospective. She notes that the land plays a central role, not as traditional painted landscape, but as a pictorial record demonstrating that Native people have always been part of the land. “These are my stories; every picture, every drawing, is telling a story,” Smith says. “I create memory maps.”

Visit the artist’s website here.

Kay WalkingStick

Kay WalkingStick, a citizen of the Cherokee Nation of Oklahoma and Anglo, has embraced the duality of her ethnicity in her artwork. Proud of her Cherokee father and raised off the reservation by her Scottish-Irish mother, WalkingStick wasn’t willing to deny her ancestry for the sake of being recognized as a contemporary artist.

Born in 1935, the artist went on to attend the prestigious Pratt Institute and earned an MFA. She later received awards for her work from the National Endowment of the Arts; the Joan Mitchell Foundation; the Women’s Caucus for Art; and the Lee Krasner Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Pollock-Krasner Foundation, among others.

Remembering her years as a young aspiring painter, WalkingStick recalls being admonished by mentors and gallerists “not to pigeonhole yourself by making ethnic work” and “not to show your work with other ‘Indians’ ”—advice she actively ignored.

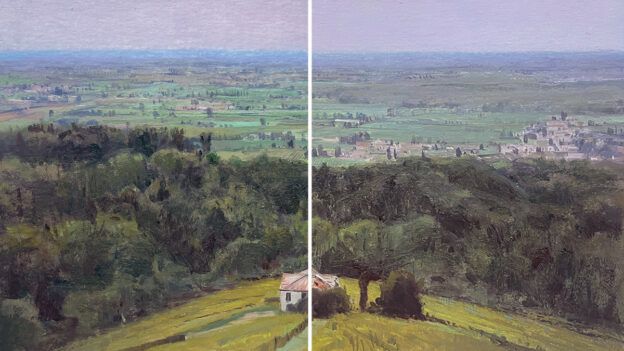

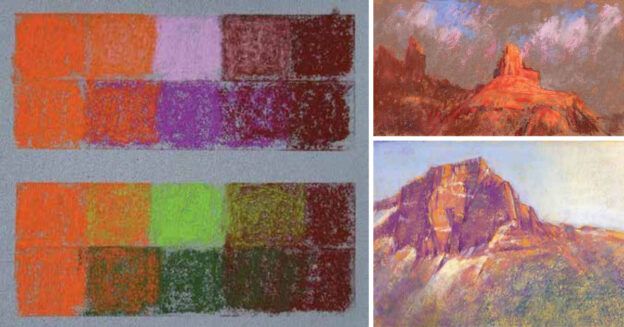

WalkingStick uses the visual language of contemporary abstraction, particularly in landscape painting, while never losing sight of the deeper meaning implied by her use of Native iconography in the structure of the work. A decidedly feminist strength, fostered by her mother, found fertile ground in early paintings. Several of her works are in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), in New York City, and the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), in Washington, D.C.

In a recent discussion with MoMA curators about the artist’s works in their collection, WalkingStick elaborated on her personal history and how it has influenced her development as an artist. “It’s important to recognize that I was dealing not only with these ideas about my heritage, but also with how to make paintings that I thought were new-looking and were totally mine,” she says. “This idea of making something that’s totally mine was always important to me. I’m not sure why, but it is the truth. I wanted them to be individual things.”

In Wampanoag Coast, Variation II, for example, a turbulent seascape of blue-green waves under a cloud-swept sky, WalkingStick reminds viewers that the former Indigenous inhabitants of this particular coastline may no longer be evident. By floating a pattern associated with Native pottery and textiles on top of the image, she conveys that their memory cannot be erased. The painting is included in the New-York Historical Society’s 2023 exhibition, “Nature, Crisis, Consequence.” The curators selected work that addresses the social and cultural impact of environmental crises on different U.S. communities throughout history.

WalkingStick continues to create work that reframes that history in terms of her experience as a Native American. Visit the artist’s website here.

Mario Martinez

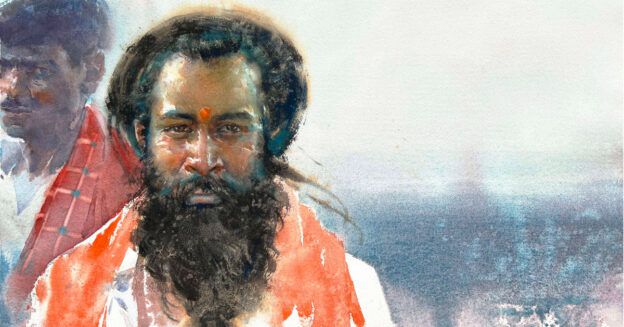

There’s no signature, or identifiable, Native style of contemporary art-making. Indigenous artists are actively making art on every continent. For some, the emphasis of their practice is on their fraught history—a history of colonization and nation-building constructed on their ancestors’ remains.

Others, like Mario Martinez, adopt an artistic vision that appears to be integrated with a decidedly 20th-century Abstract Expressionist stance. Although we can find elements in his painting akin to the energy of Willem de Kooning (Dutch-American, 1904–97) or the flittering forms reminiscent of Arshile Gorky (Armenian-American, 1904–48), Martinez says, “I’m part of a 40,000-year tradition.” In his studio, Martinez seamlessly integrates pre- and post-colonial American painting traditions. His memories of ancestral lands still linger, and they’re now enveloped by his experiences visualized in paintings of his adopted New York City home.

Born in 1953, Martinez is a member of the Pascua Yaqui Tribe, of Arizona. He majored in art at Arizona State University and earned his MFA at the San Francisco Art Institute. Like many other Native traditions, the Yaqui religion was founded on a deep reverence for nature. Martinez acknowledges that reverence in Green Forest, an acrylic painting teaming with life. Abstract forms hint at the magical sights and sounds of the forest and mingle among the vertical lines suggesting trees. Meanwhile, he fully integrates his New York experience with his Yaqui sensibilities in the softened yet saturated color in New York, Desert Day Dream.

In 2005, Martinez was the subject of a mid-career retrospective at the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian, in New York City. The museum acquired his monumental abstract painting Brooklyn from that exhibition for its permanent collection. More recently, Martinez was included in “Stretching the Canvas: Eight Decades of Native Painting,” a widely publicized show that featured more than 30 indigenous artists from the Smithsonian’s collection, including the other artists highlighted here.

Martinez has received numerous grants and awards, including a Native Arts Research Fellowship, National Museum of the American Indian; an Artist in Residence Fellowship, National Museum of the American Indian; a Joan Mitchell Foundation CALL Grant; a Robert Rauschenberg Foundation Residency; and the Murray Reich Distinguished Artist Award. The artist’s work is featured in the collections of numerous museums and institutions across the country, such as the Museum of Contemporary Native American Art, in Santa Fe; the Eiteljorg Museum, in Indianapolis; the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian; and the Heard Museum, in Phoenix, Ariz., among others. He continues to work in his Brooklyn, N.Y., studio.

Yatika Starr Fields

What accomplished activist artist can also claim to be an endurance runner and cyclist? The answer to that combination of talents is the multifaceted Yatika Starr Fields. Born in 1980 in Tulsa, Okla., he’s a member of the Bear Clan, and his lineage includes the Cherokee, Creek and Osage Tribes. His parents, Tom and Anita Fields, are also Native artists. Although he’s the youngest of the artists featured here, he has accumulated a long list of accomplishments. He has participated in more than 40 solo and group exhibitions at museums and other venues across the U.S. and Europe.

Fields is known for the explosive energy evident in every brushstroke or gesture, whether applied to a wall-sized mural, a collage on paper or an oil painting on canvas. Many of his paintings, particularly those infused with abstract elements and techniques that he learned through graffiti art, seem to have burst into existence. The shear physicality of Fields’ painting method—using full-body motion—is conducive to creating large murals, which he has done in front of audiences. “It’s almost choreographed, like I’m putting on a performance,” Fields says.

It was following his years of study from 2001 to 2004 at the Art Institute of Boston that he became enamored of street art. “Graffiti is very confrontational,” Fields says. “This was me rebelling against the western idea of fine art. It was me finding another new voice and new style and rejecting everything I had just learned [in college].”

While conscious of his ancestral ties to his community since childhood, it was in 2016, when he joined the Sioux Tribe in its protest at Standing Rock against the Dakota Access Pipeline, that he became an activist. The oil pipeline posed serious environmental concerns, threatening water resources and sacred tribal lands. Massive protests ensued, generating global reactions against the pipeline.

Much of the artwork Fields produced in 2017 reflects his experience at Standing Rock. Paintings such as Samí Solidarity (Standing Rock) and White Buffalo Calf Women’s March (Standing Rock) highlight his ability to make powerful, explicitly figurative work. Fields is equally comfortable morphing figurative elements into symbolic abstract forms, like those in Caution.

In addition to his art-based activism, Fields finds inspiration in running ultramarathons—races over 26.2 miles—annually. He also finds similarities between running and painting. In a 2019 article in Tulsa People magazine, when he was in the Netherlands completing a mural in the Museum Volkenkunde after competing a 90-mile trail race through the Alps, Fields said, “I’m still figuring it out, but I think it’s the same thing: It’s about being patient with results. It’s about being consistent to the devotion of the art. Running is an art form. Painting is an art form. Your body is an art form. Movement is an art form. Running is colorful; painting is colorful. Running is poetry; painting is poetry. I’ve found a really eloquent correlation between the two that’s kind of hard to describe, but it’s about movement.”

Visit the artist’s website here.

These four prominent Native American artists, as well as so many others, are creating works that, while intimately personal, inform our understanding of the world.

About the Author

Cynthia Close (cynthiaclose.com) earned an MFA from Boston University and worked in various art-related roles before becoming a writer and editor.

Enjoying this article? Sign up for our newsletter!

From Our Shop

Join the Conversation!